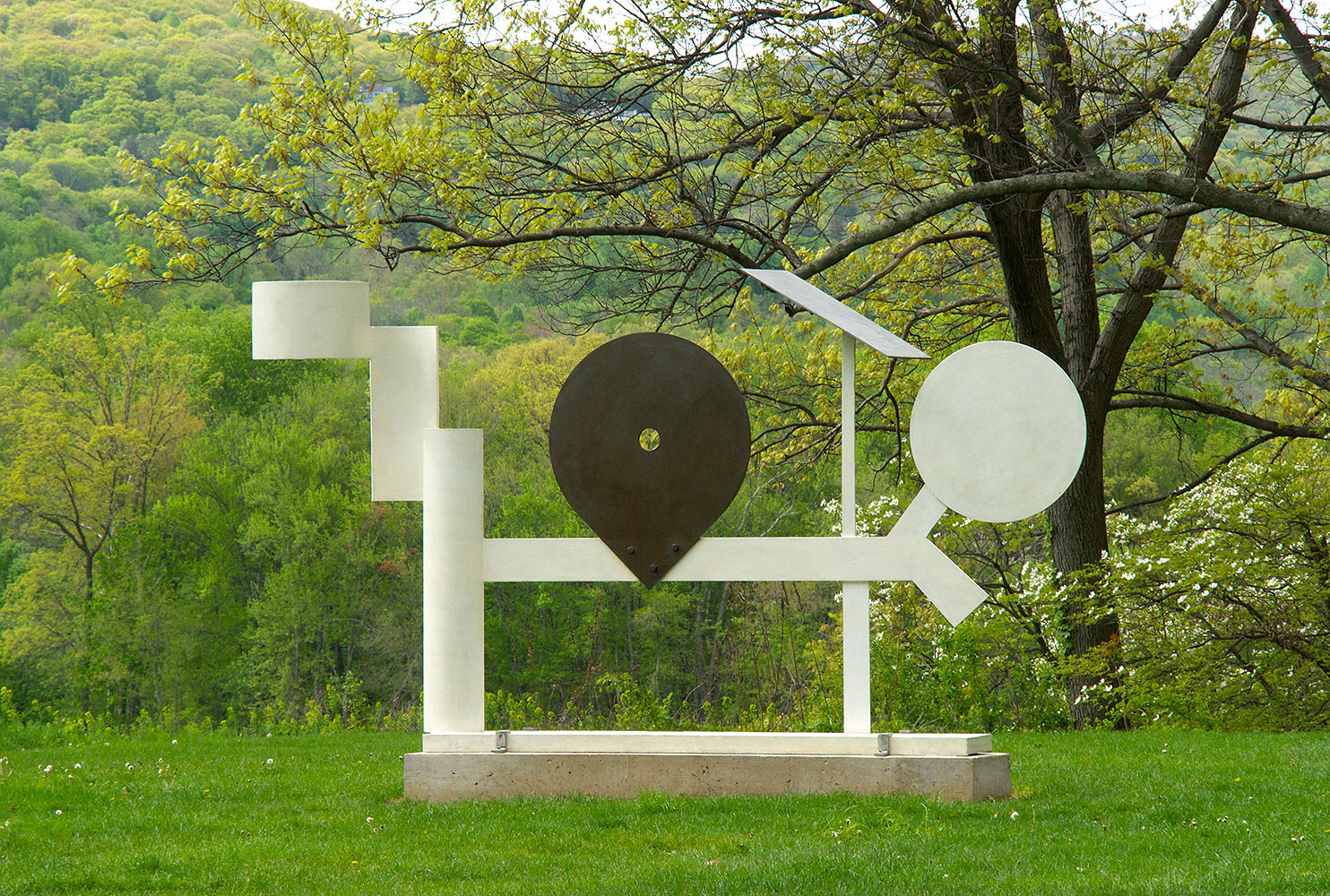

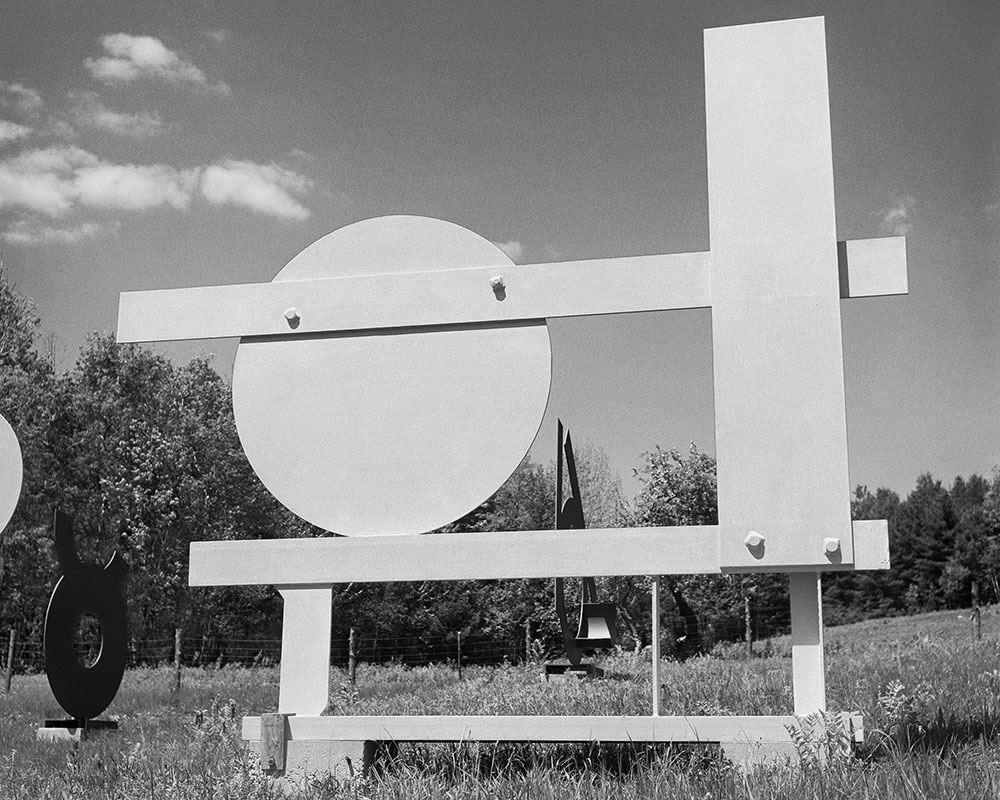

“Primo Piano I”, 1962

Painted steel

110 x 144 x 21 in. (279.4 x 365.8 x 53.3 cm)

Roberts Family Collection

Beginning in the early 1950s, Smith often worked in series, modifying the compositional elements of each iteration within a sculptural group. In explaining the significance of the title of his Primo Piano series, the artist said: “This group [is] called Primo Piano, only because on the first floor nothing happens—whatever takes place is on the second floor.” Primo Piano I, which typifies the geometric flatness characteristic of the series, creates moments of visual framing through cutouts, angular junctions, and enclosed negative space. This exhibition marks the first time the three works in the series have been displayed as a group.

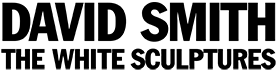

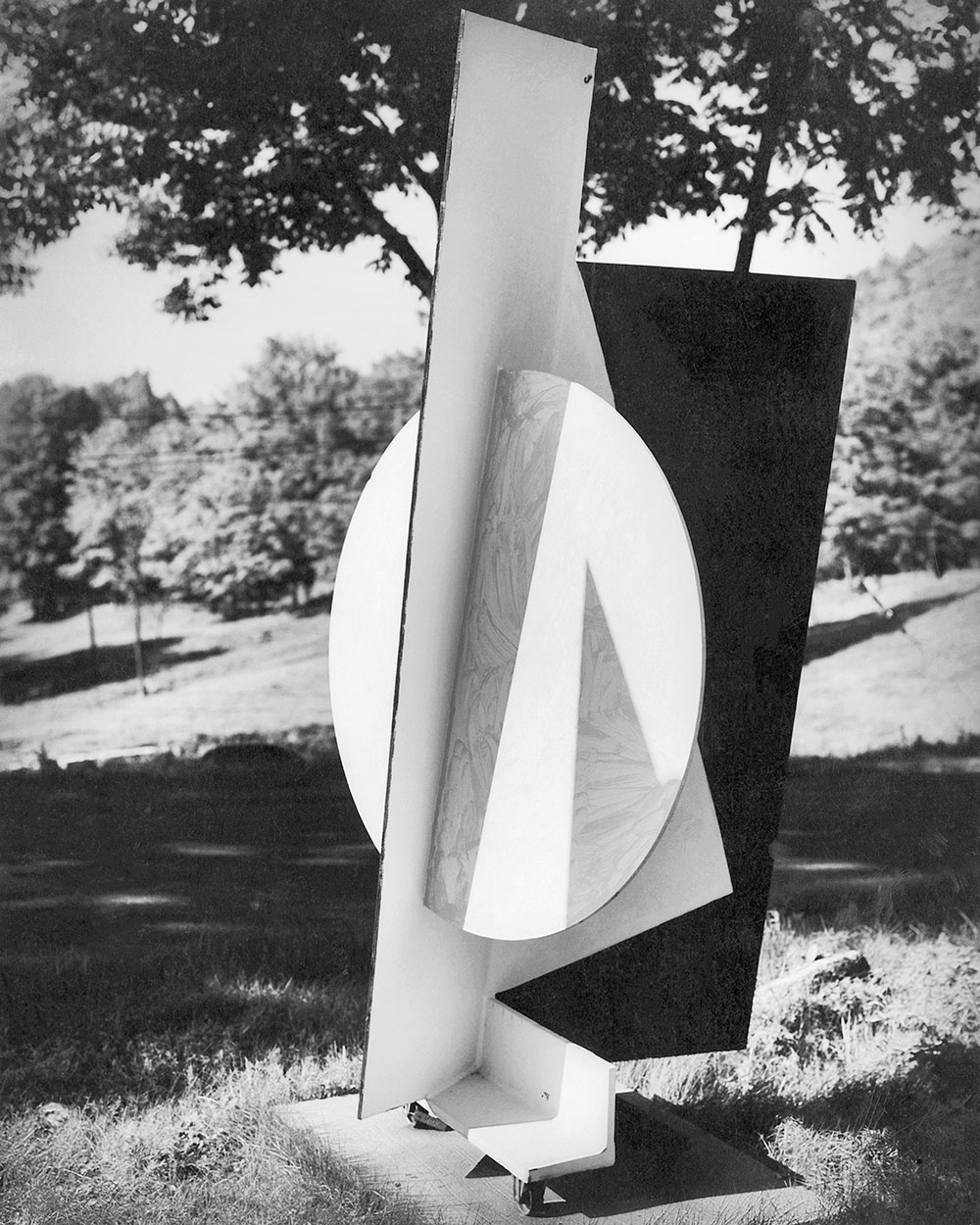

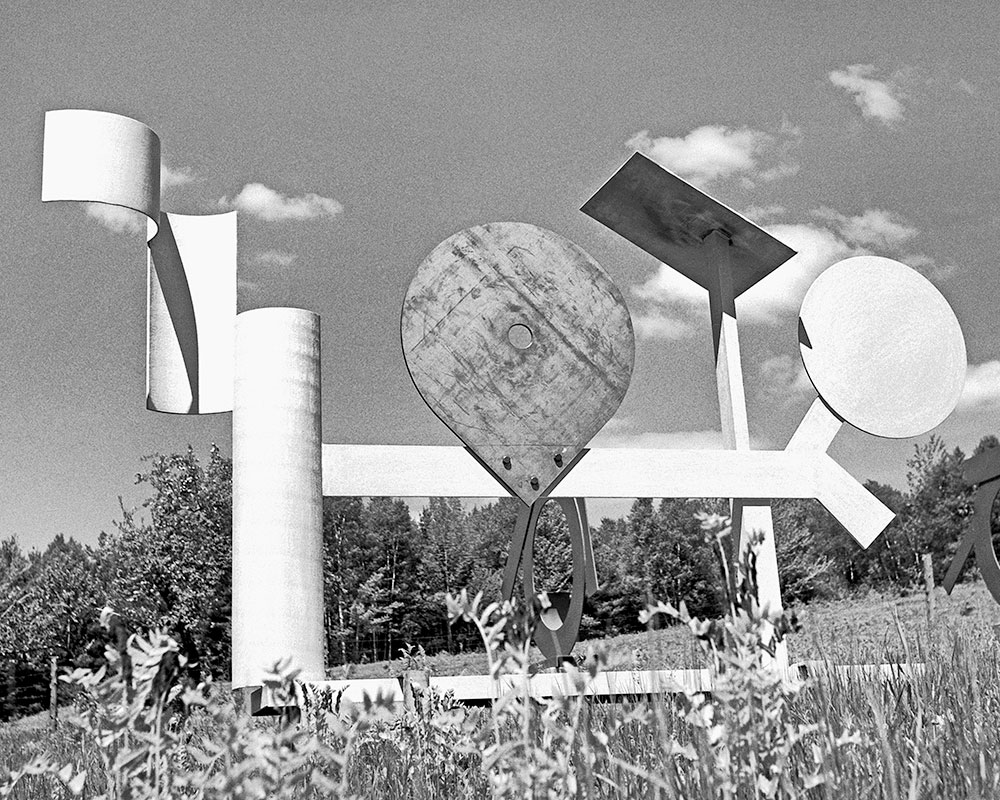

“Primo Piano II”, 1962

Painted steel, stainless steel, and bronze

85 x 158 x 15 in. (215.9 x 401.3 x 38.1 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In Primo Piano II, a bare teardrop shape cut from industrial bronze plate contrasts with painted white surfaces, demonstrating Smith’s frequent interest in both textural and color differences within a sculpture’s overall composition. The artist sometimes spoke of white paint as a “primer” for later applications of color, although white was not always the base coat; Smith often layered yellow, green, and even red paint on his works before applying one or more additional coats of white. Leaving the sculptures white while he contemplated their final color, the artist would install the works outdoors, sometimes waiting months or even years before determining that a piece was finished.

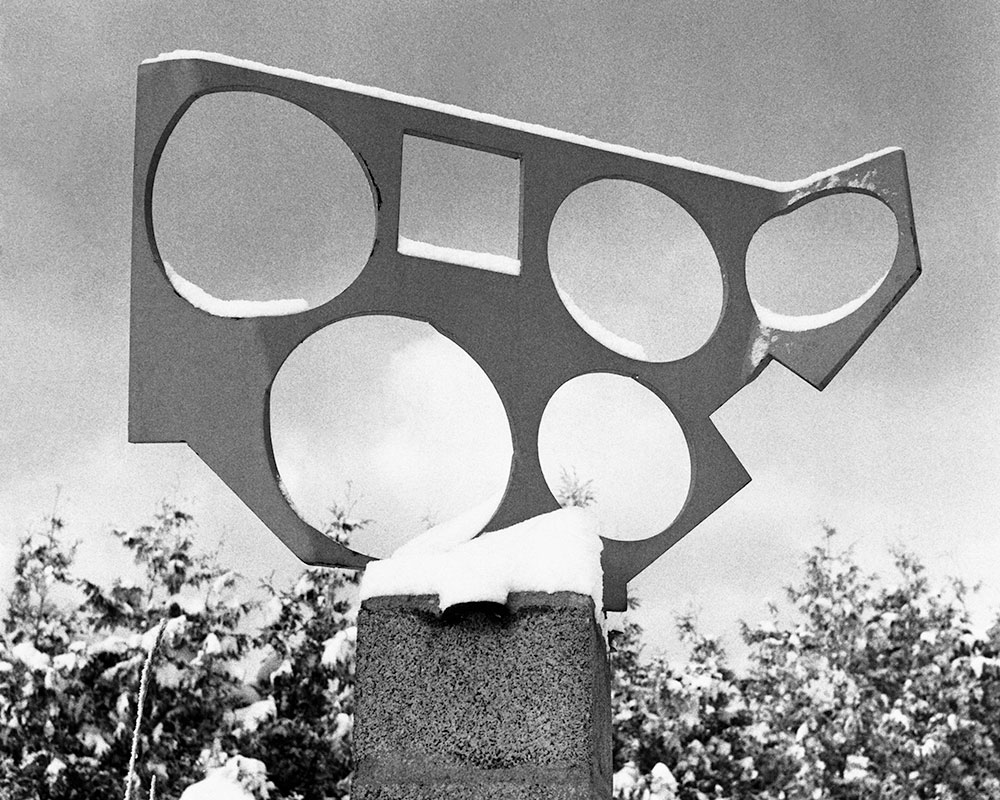

“Primo Piano III”, 1962

Painted steel

124 x 146 x 19 in. (315 x 370.8 x 48.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Smith took great care installing his sculptures in groups in the fields surrounding his Adirondack studio in Bolton Landing, NY, in conversation with the mountainous landscape. Primo Piano III, the last in the Primo Piano series, with its flat array of three simple and assertive geometric forms supported along a sturdy horizontal, creates a visual “cutout” in the landscape. Smith was interested in breaking down the distinctions between painting and sculpture. The white sculptures, like Primo Piano III, create in three-dimensions the inversion of figure and ground that he was also exploring in his spray enamel paintings, some of which are displayed in the museum building. This dramatic effect is seen when viewing these works installed outdoors, a viewshed which closely approximates Smith’s own installation of the white sculptures on his property at Bolton Landing.

Circle and Box (Circle and Ray), 1963

Painted steel

119 1/2 x 29 1/4 x 22 ½ in. (303.5 x 74.3 x 57.2 cm)

Irma and Norman Braman Art Foundation, Florida

Smith acquired his welding skills as a young man by working in the Studebaker automobile factory in South Bend, Indiana, and he later assembled locomotives and destroyer tankers in Schenectady, New York, during World War II. Drawn to the materials and techniques of machine welding, Smith often used industrial automobile enamels to paint his works. In Circle and Box (Circle and Ray) disparate elements that reflect Smith’s experience in industrial metalsmithing are welded together to form a collage-like composition, which the artist then unified with monochrome coats of white paint.

2 Circles 2 Crows, 1963

Painted steel

68 3/4 x 125 x 8 1/4 in. (174.6 x 317.5 x 21.0 cm)

Irma and Norman Braman Art Foundation, Florida

Smith once said that his sculptures “can begin sometimes when I’m sweeping the floor and I stumble and kick a few parts that happen to throw into an alignment that . . . sets off a vision of how it would finish if it all had that kind of accidental beauty to it. I want to be like a poet, in a sense.” In 2 Circles 2 Crows, two found metal circles frame cutout scraps from another work (2 Circle IV, 1962), which became the titular elements seen here. This work celebrates the discrepancies in repetition between the two forms, while exemplifying the artist’s interest in combining found elements to compose a singular sculpture.

Untitled, 1963

Painted steel

88 x 33 x 26 in. (223.5 x 83.8 x 66 cm)

Collection of Candida Smith; courtesy the Estate of David Smith, New York

This untitled work invites the viewer to walk around the sculpture, directing an experience that incorporates the landscape and the movements of the viewer. The four planar sections, set perpendicular to one another, appear, disappear, and reappear as they are foreshortened or hidden depending on the viewer’s position—revealing rectangular incisions and circular cutouts that frame unexpected vistas. The sculpture’s construction precludes viewing all four planes simultaneously; only in the viewer’s imagination can the work be seen in its entirety.

Untitled (Standing Figure), 1932

Coral and wire on terra cotta base

5 5/8 x 2 1/2 x 2 1/2 in. (14.3 x 6.4 x 6.4 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

From October 1931 to June 1932, Smith and his first wife, Dorothy Dehner, a sculptor and painter, lived and worked on the island of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. This time in the Caribbean proved formative for Smith, as he began creating sculpture using the natural materials found along the coastlines and photographing abstract compositions made from various found objects, like coral or driftwood. This untitled figure, which uses growths of coral to evoke appendages, is likely the first sculpture Smith made.

Untitled (Standing Figure), 1932

Coral on artist’s wood base

3 1/4 x 1 3/4 x 1 in. (8.3 x 4.45 x 2.54 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Untitled (Construction), 1933

Coral, stones, lead, copper wire, and brass rods on artist’s wood base

15 x 7 x 3 in. (38.1 x 17.8 x 7.6 cm)

Collection of Jon Shirley

Construction (Lyndhaven), 1932

Coral, iron, lead, and painted wire on artist’s

painted wood base

25 3/4 x 7 3/4 x 5 in. (65.4 x 19.7 x 12.7 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Untitled, 1955

Painted steel

29 x 45 x 34 in. (73.7 x 114.3 x 86.4 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Tanktotem IX, 1960

Painted steel

90 x 33 x 24 1/8 in. (228.6 x 83.8 x 61.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Tanktotem VII, 1960

Painted steel

84 1/2 x 37 x 14 1/8 in. (214.6 x 94 x 35.9 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Tanktotem VII is one of the last in Smith’s Tanktotem series (1953–60), which comprises ten sculptures, each incorporating parts of prefabricated boiler tank ends. The work reflects two aspects central to the artist’s creative interest: an admiration for the working methods traditionally linked to industrial labor, and an attraction to the verticality of the totemic form with its connections to ancient sculptural traditions as well as to early modern abstraction. Smith treated the surface of Tanktotem VII like a three-dimensional canvas, and created a painting whose forms are in dialogue with the geometry of the sculptural object.

Black White Forward, 1961

Painted steel

88 1/8 x 48 x 38 in. (223.8 x 121.9 x 96.5 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

4/28/61, 1961

Painted steel

88 1/2 x 46 x 39 in. (224.8 x 116.8 x 99.1 cm)

The Lipman Family Foundation

Smith considered the painted surface of a sculpture of equal importance to form, saying, “It is obvious that there exists a logic of color relationship to sculptural form just as there exists a logic in the scale of sculpture.” In this work, named after the date of its completion, a light-hued disc appears like a face gazing upward on top of what Smith described as a “moon blue” armature. The choice of colors gives the sculpture an anthropomorphic quality as the lower portion of the sculpture, like a body, is darker than top portion, a disc-like head; this strategy Smith employed in a number of his painted-steel sculptures from the 1960s. This is the first time this work has been exhibited publicly.

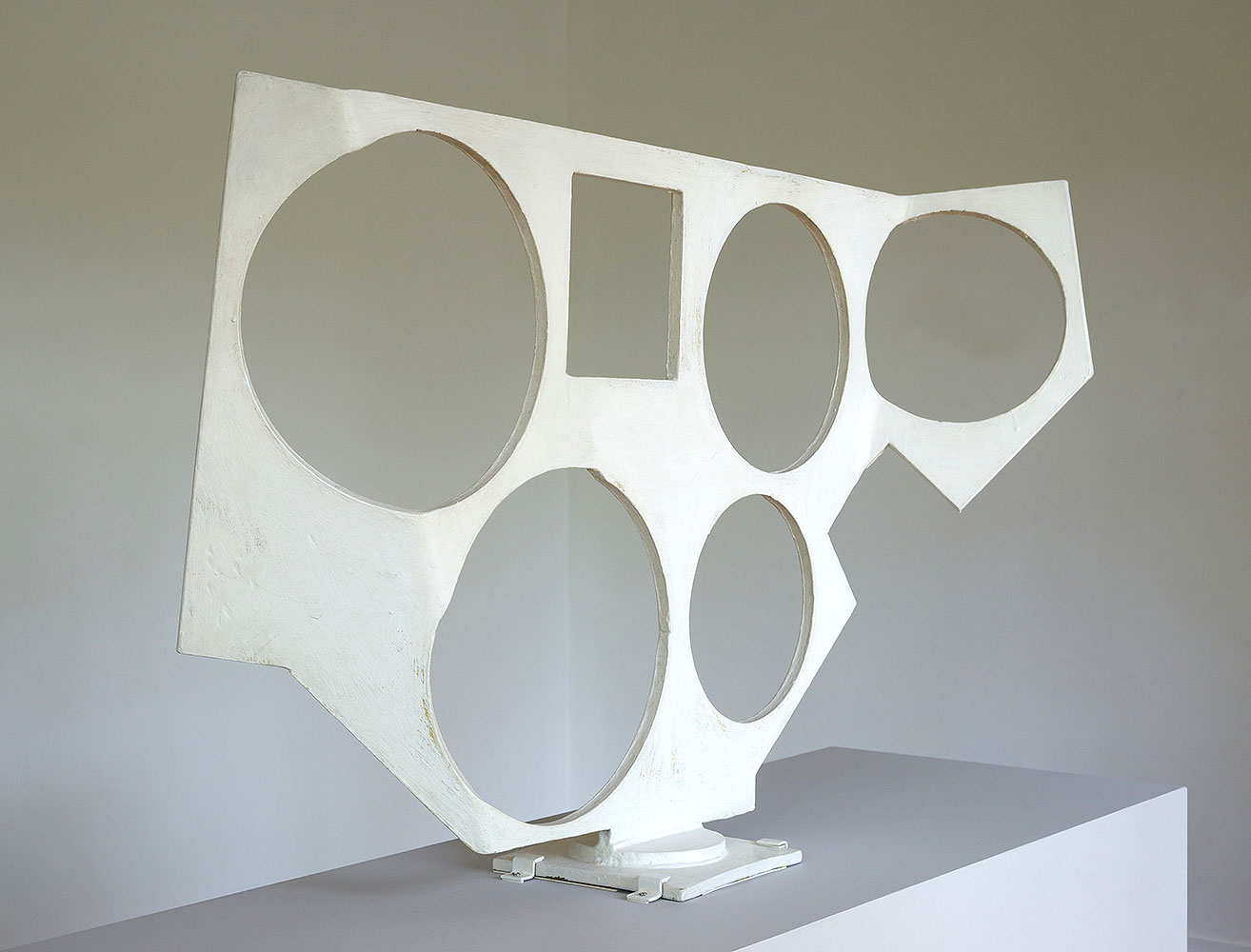

ΔΣ 1958, 1958

Spray enamel on paper

17 1/2 x 11 3/8 in. (44.5 x 28.9 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Untitled, 1958

Spray enamel on canvas

18 x 17 in. (45.7 x 43.2 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

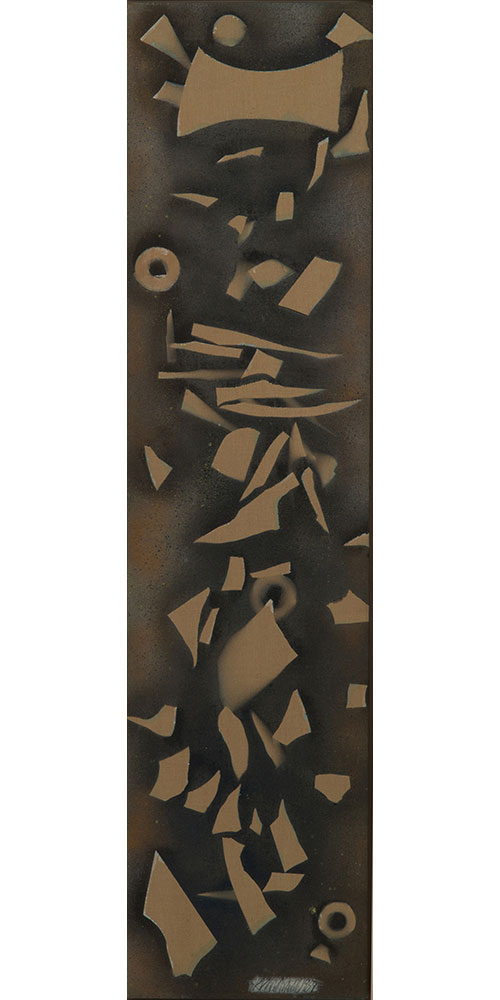

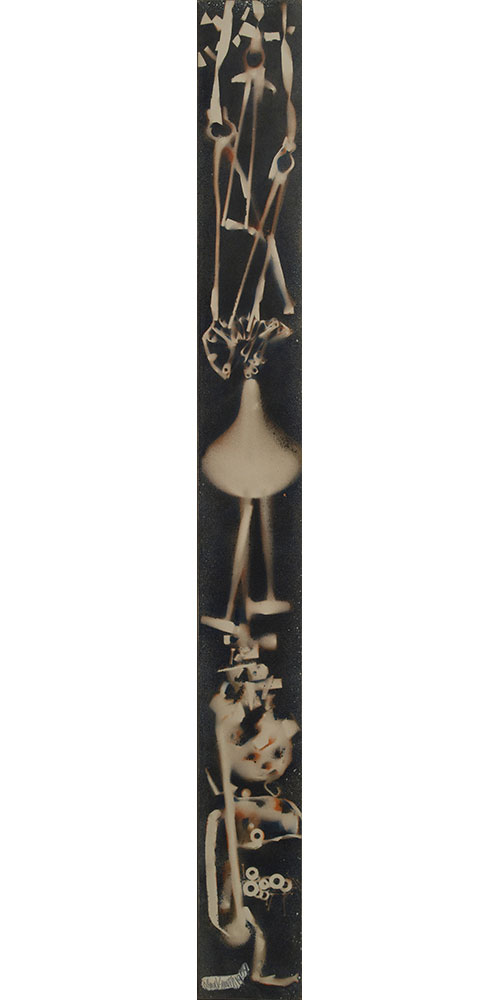

Night Window, 1959

Spray enamel on canvas

72 x 17 5/8 in. (182.9 x 44.8 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Night Window, 1959

Spray enamel on canvas

72 x 17 5/8 in. (182.9 x 44.8 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In order to create his “spray” paintings, which he began in 1957, Smith would place objects on an unstretched, primed canvas and spray enamel onto the surface using the same technique as for painting cars. When the objects were removed, what remained was a ghostly white absence against a hazy halo of spray paint. These works were essential to Smith’s understanding of his own sculptural practice: as the artist once commented, he was interested in “dream images, subconscious images, after-images. They’re like the series of paintings I made where the image was the hole from which the sculpture was removed. What was formed there was the after-image.” All trappings of a blacksmith’s shop—nuts, bolts, tongs, two-headed hammers, and a bellows for stoking a flame—comprise the “after-images,” or missing sculptural objects, in this spray painting.

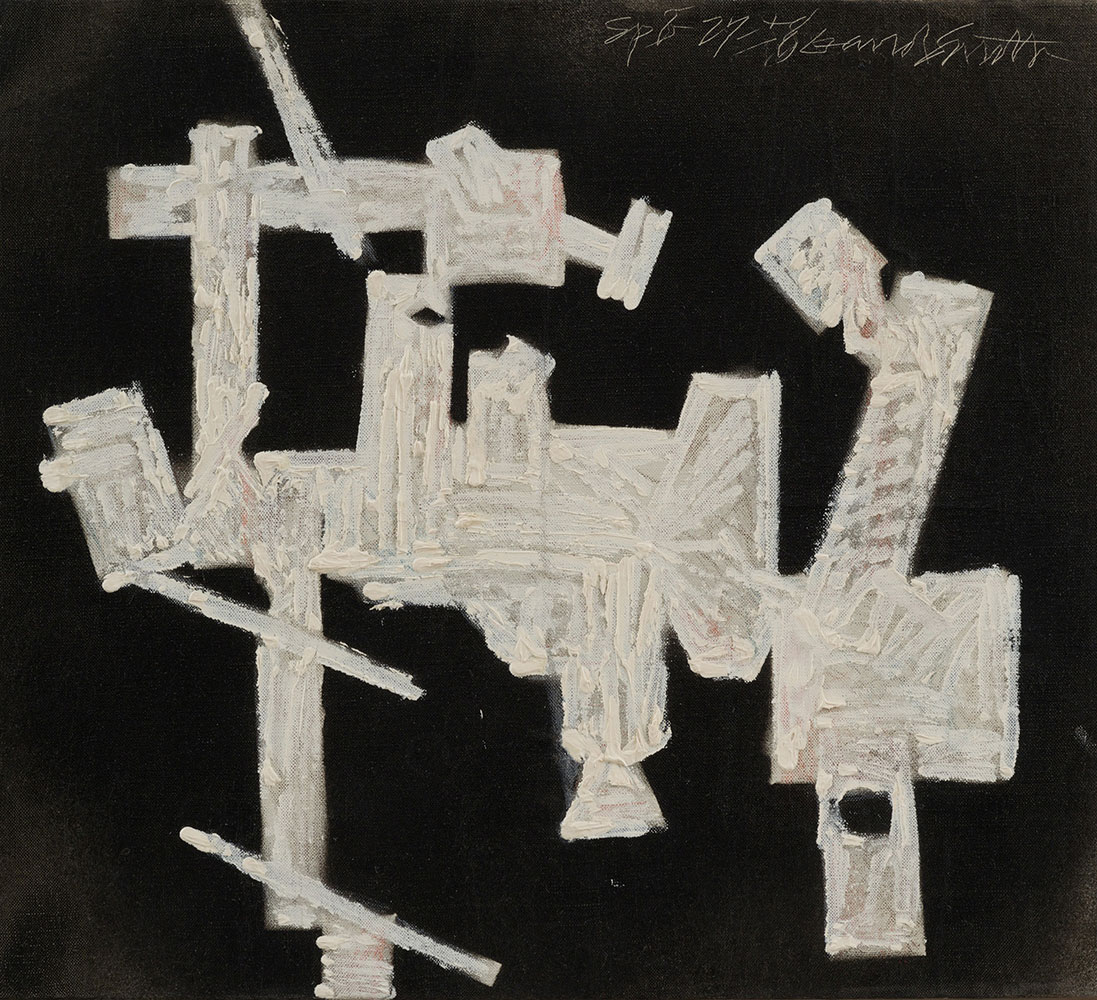

Untitled, 1958

Oil on canvas

18 1/2 x 19 in. (47 x 48.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

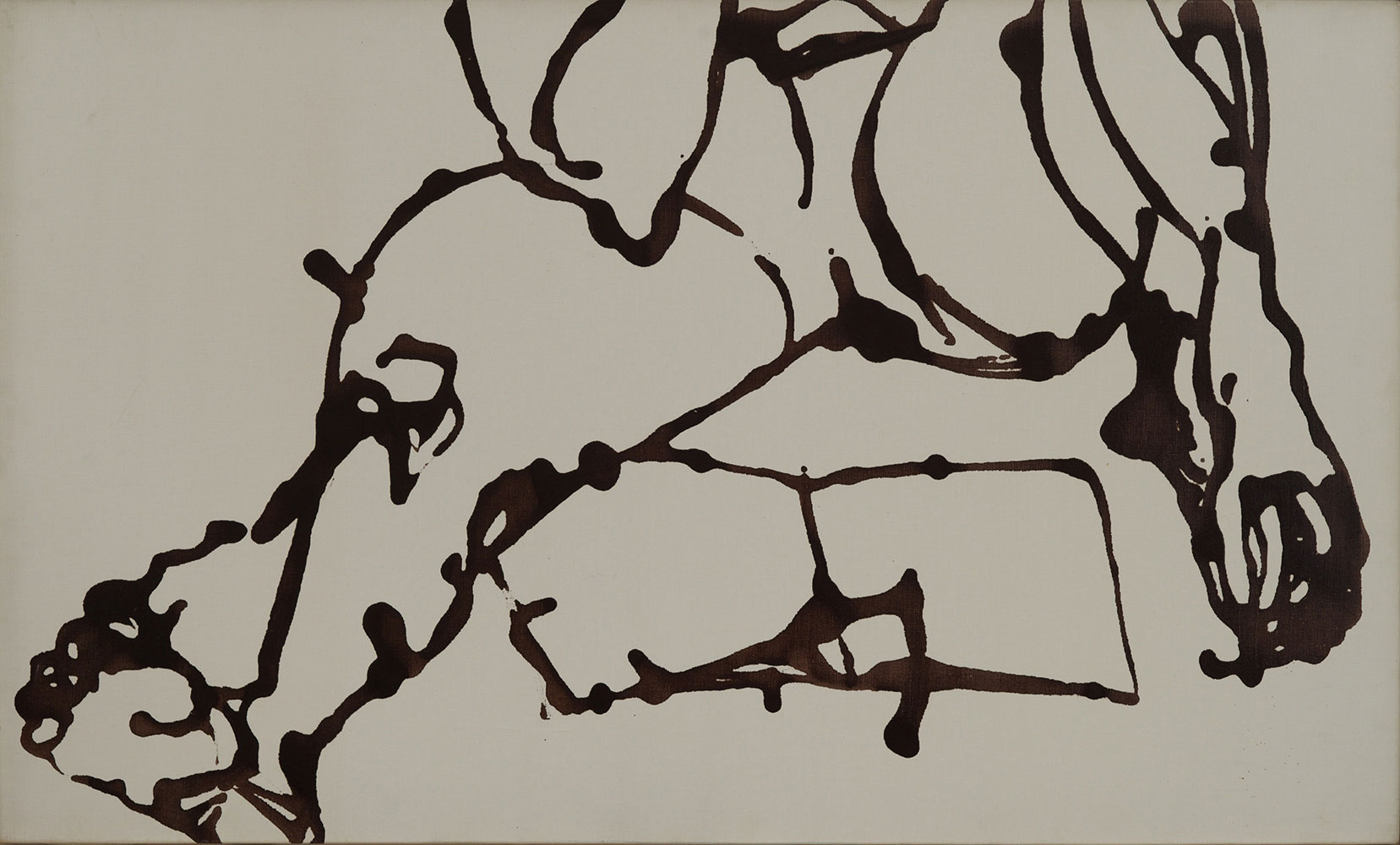

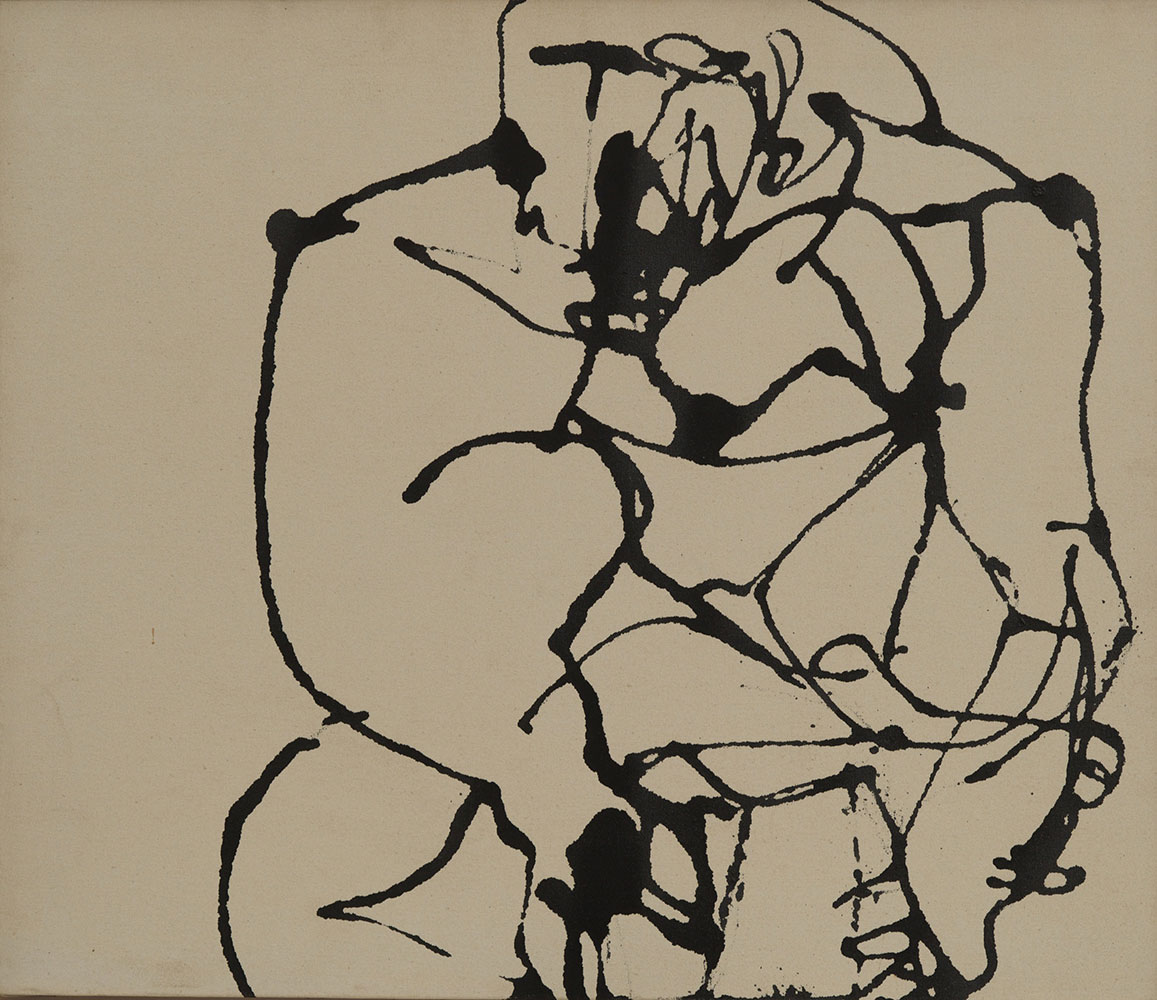

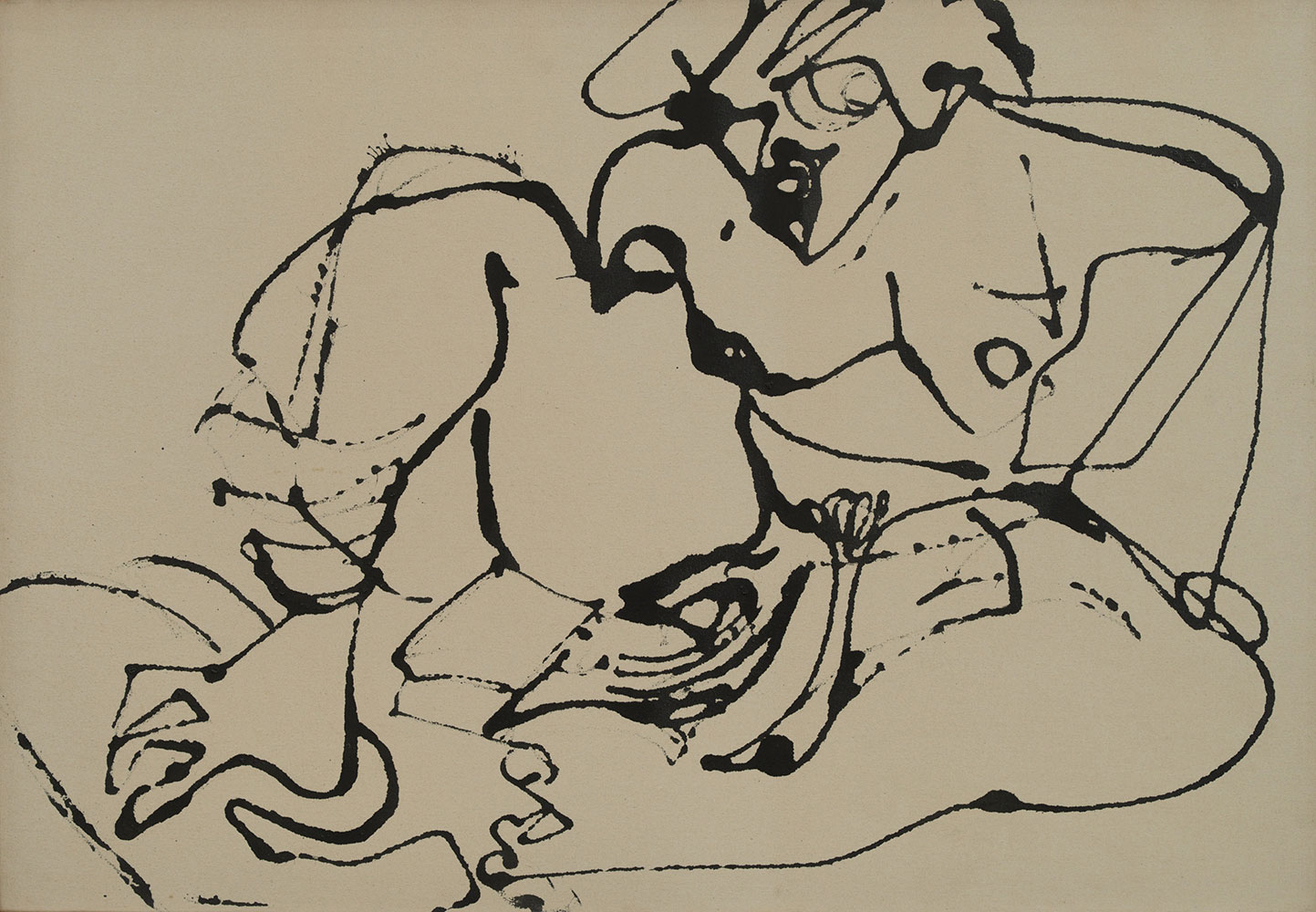

Untitled (Nude), 1964

Enamel on canvas

24 1/2 x 40 1/4 in. (62.2 x 102.2 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Untitled (Nude), 1964

Enamel on canvas

26 1/2 x 31 in. (67.3 x 78.7 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Untitled (Nude), 1964

Enamel on canvas

27 1/2 x 39 3/4 in. (69.9 x 101 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

To achieve the distinctive “drip” characteristic of this late series of nude drawings, Smith would lay a primed, unstretched piece of canvas horizontally on a table or on the floor. Then, using an ear syringe filled with black enamel, he would squeeze the paint onto the canvas, tilting the surface to create spontaneous splashes and drips that evoke the contours and shadows of a woman’s body. Here, the swift, inky lines of the enamel suggest a crouched woman reading. Because Smith allowed the whiteness of the canvas to come to the fore of in this series of contour paintings, the black gestural drips enclose white shapes, which confuse positive and negative space.

“2 Circles 2 Crows” (with “Cubi VI” in the Background), Bolton Landing, 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“4/28/61” at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“4/28/61” at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Black White Backward” (in the Doorway of Workshop) at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Black White Backward” (in the Doorway of Workshop) at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Smith captured in this photograph his sculpture, Black White Backward, in the doorway of his studio, like a frame within a frame. A single beam of light cascades across the disc shape that centers the composition, demonstrating the artist’s interest in how light interacts with the surface and form of his works. White rectangles overlap gray circles that overlap black rectangles; the overall effect flattens the sculpture into an abstraction of intersecting geometric planes. Black White Backward is a companion piece to Black White Forward (1961), included in this exhibition.

“Black White Backward” (in the Doorway of Workshop) at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Black White Backward” at Bolton Landing, c. 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Untitled 1955” at Bolton Landing, c. 1955

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Untitled 1955” at Bolton Landing, c. 1955

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Lunar Arc” (1961), date unknown

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

In this photograph, Lunar Arc—one of the eight works left painted white upon Smith’s untimely death—appears like a crescent moon against a nearly cloudless sky. Photographing his works in the landscape provided Smith the opportunity to understand his own practice more deeply. Through these images he was interested in documenting what he called the “eidetic image,” or how a sculpture’s existence as an image in the viewer’s mind supersedes its presence as a physical object. In this vein, Lunar Arc appears almost like a white cutout against the landscape instead of a three-dimensional sculpture.

“Oval Node” (with “Volton XI”, “Voltri-Bolton VIII”, “Volton XXIV”, “Volton XVIII” in Background), Bolton Landing, c. 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Oval Node, seen in these two photographs, is one of the eight sculptures that remained painted white upon Smith’s death, in 1965. Although it is not certain that Smith intended white to be the final color, the work remained white in the two years following its initial completion, in 1963, during which time the artist photographed it in the fields of Bolton Landing. In this image Smith uses light to play off the geometric depressions in the work’s large oval form. One photograph shows the way sunlight creates parallel hollows on the surface of the sculpture, while the shadowy appearance of the other demonstrates how the rectangular indentations can catch light and suggest depth. The way light interacts with the surface of a work was integral to the way Smith visually investigated his sculpture, as seen in many of the artist’s photographs of his works outdoors.

“Oval Node” (with “Voltri-Bolton V”, “Voltri-Bolton X”, and “Voltri-Bolton IV” in Background), Bolton Landing, c. 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Oval Node, seen in these two photographs, is one of the eight sculptures that remained painted white upon Smith’s death, in 1965. Although it is not certain that Smith intended white to be the final color, the work remained white in the two years following its initial completion, in 1963, during which time the artist photographed it in the fields of Bolton Landing. In this image Smith uses light to play off the geometric depressions in the work’s large oval form. One photograph shows the way sunlight creates parallel hollows on the surface of the sculpture, while the shadowy appearance of the other demonstrates how the rectangular indentations can catch light and suggest depth. The way light interacts with the surface of a work was integral to the way Smith visually investigated his sculpture, as seen in many of the artist’s photographs of his works outdoors.

“Primo Piano I” (with “Lunar Arc”, “Primo Piano II,” “Zig IV”, “Primo Piano III” and “Circle III” in Background), Bolton Landing, c. 1962

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Primo Piano II” (with “Circle I”, and “Primo Piano III” in Background), Bolton Landing, c. 1962

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Primo Piano III” (with “Primo Piano II”, “Circle III”, and “Circle II” in Background), Bolton Landing, 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled (Tableau), c. 1931–33

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

This Untitled (Tableau) is one of many experimental photographs created during Smith’s 1931-32 sojourn in the Virgin Islands, and demonstrates the artist’s early engagement with Surrealism, which reached its heyday in Europe by the late 1920s. The organic shape of the white coral in the foreground contrasts with the classical kneeling nude in the background, a juxtaposition that speaks to currents in Surrealist thought at the time, such as an interest in the clash between antiquity and modernity. Further in dialogue with Surrealism, the tension between figuration and abstraction within the same visual space is at the forefront of this photo. Smith emphasized the contours of the objects in the composition by scraping small lines onto the negative before generating the print; these hand-drawn details appear as faint white outlines of the nude’s thigh and the blurry coral in the background. Smith continued to understand these early coral experimentations within the context of the European avant-garde, and in 1939 he sent a number of his early photographs to Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, who was then teaching at the Institute of Design in Chicago. Though Moholy-Nagy invited Smith to teach alongside him in 1944, Smith declined the invitation as his practice in photography has shifted by that point. The artist had become fully invested in sculpture by the 1940s, using the camera instead as a means to document his work situated in the fields of Bolton Landing.

Untitled (Virgin Islands Tableau), c. 1931–32

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Coral Construction, c. 1931–32

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled (Tableau), c. 1932–33

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled (Virgin Islands Tableau), c. 1931–32

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Shell Construction, 1931

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Construction, 1931

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

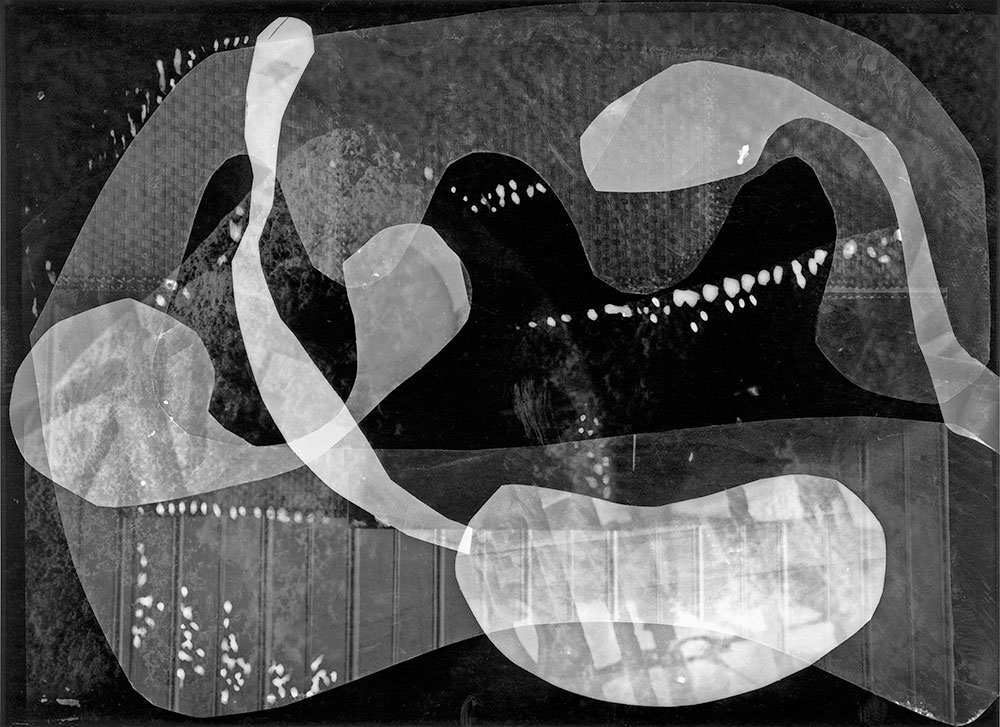

Untitled, c. 1932–35

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

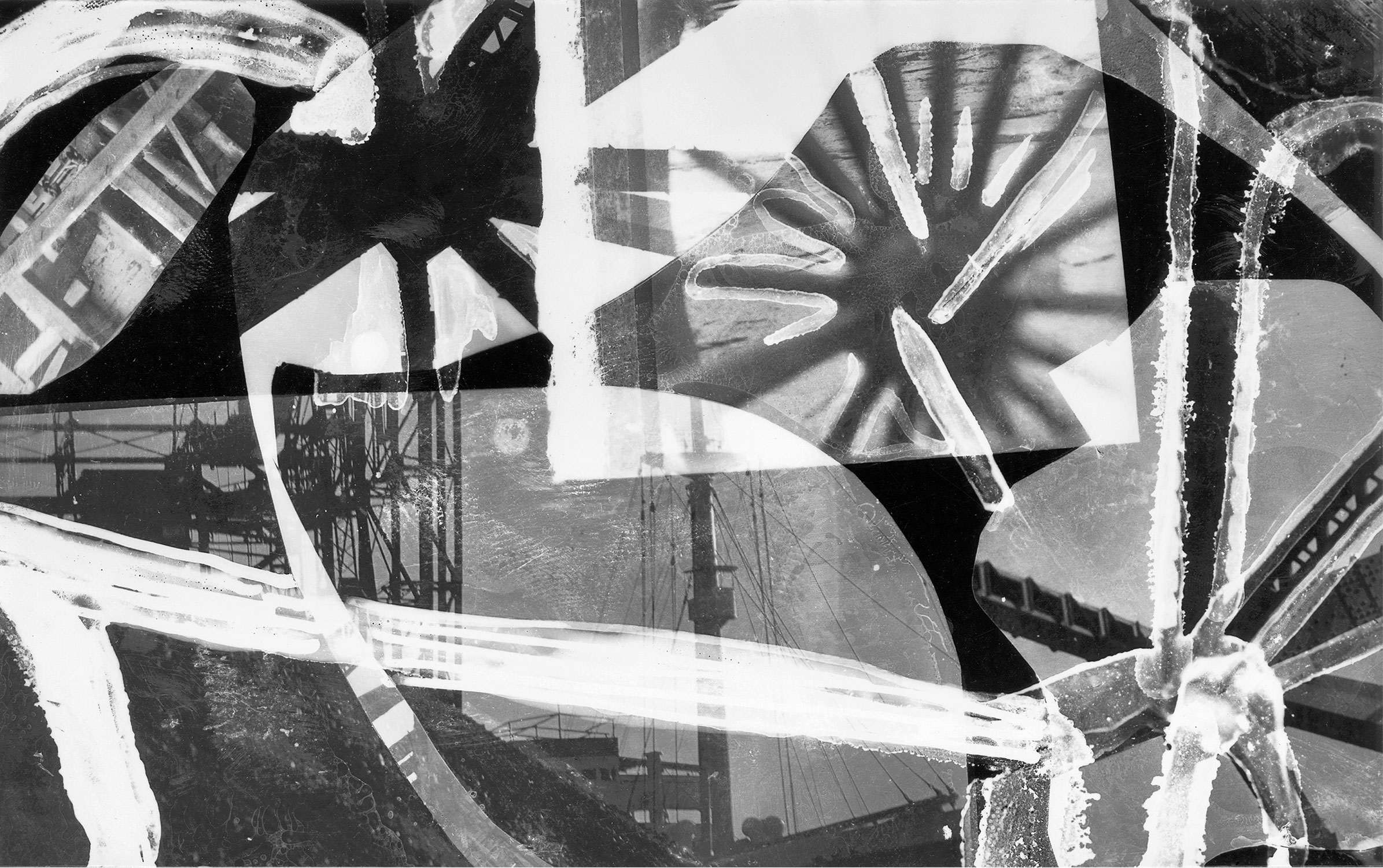

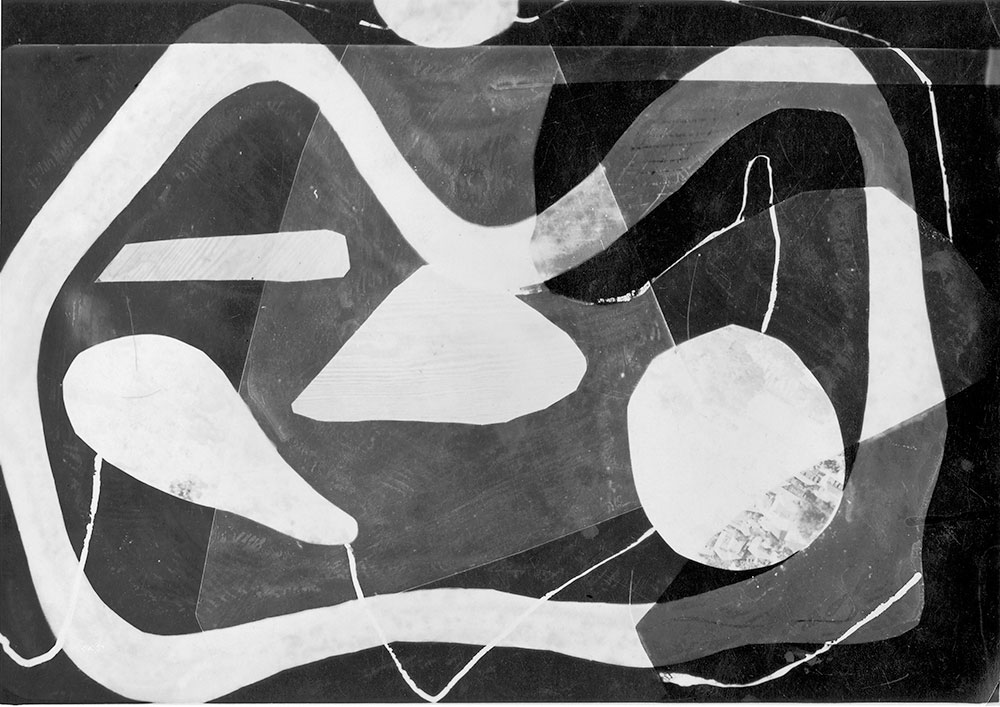

Untitled, c. 1932–35

Chromogenic black-and-white print of photocollage

5 x 8 in. (12.7 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled, c. 1932–35

Chromogenic black-and-white print of photocollage

5 x 8 in. (12.7 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Smith began making photocollages upon his return to New York from the Virgin Islands in 1932. In order to achieve the layering of shapes, textures, and images seen here, Smith sandwiched multiple negatives together before exposing the photosensitive paper that became the printed photograph. The negatives show evidence of the artist drawing or scraping shapes by hand to achieve lines and textures. The white cutout shapes and lines flatten and confuse foreground and background, echoing later strategic uses of the color white in Smith’s sculptural practice. The image, showing docks in Brooklyn, was likely taken near the Terminal Iron Works, where the artist began his first serious production of welded-steel sculpture. Though Smith would abandon this experimental mode of photography by the mid-1930s, the collage sensibility inherent to this photograph is reminiscent of his later steel and cast sculpture made from multiple found or cut forms.

Untitled (Virgin Islands Tableau), c. 1931–32

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 5 in. (25.4 x 12.7 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

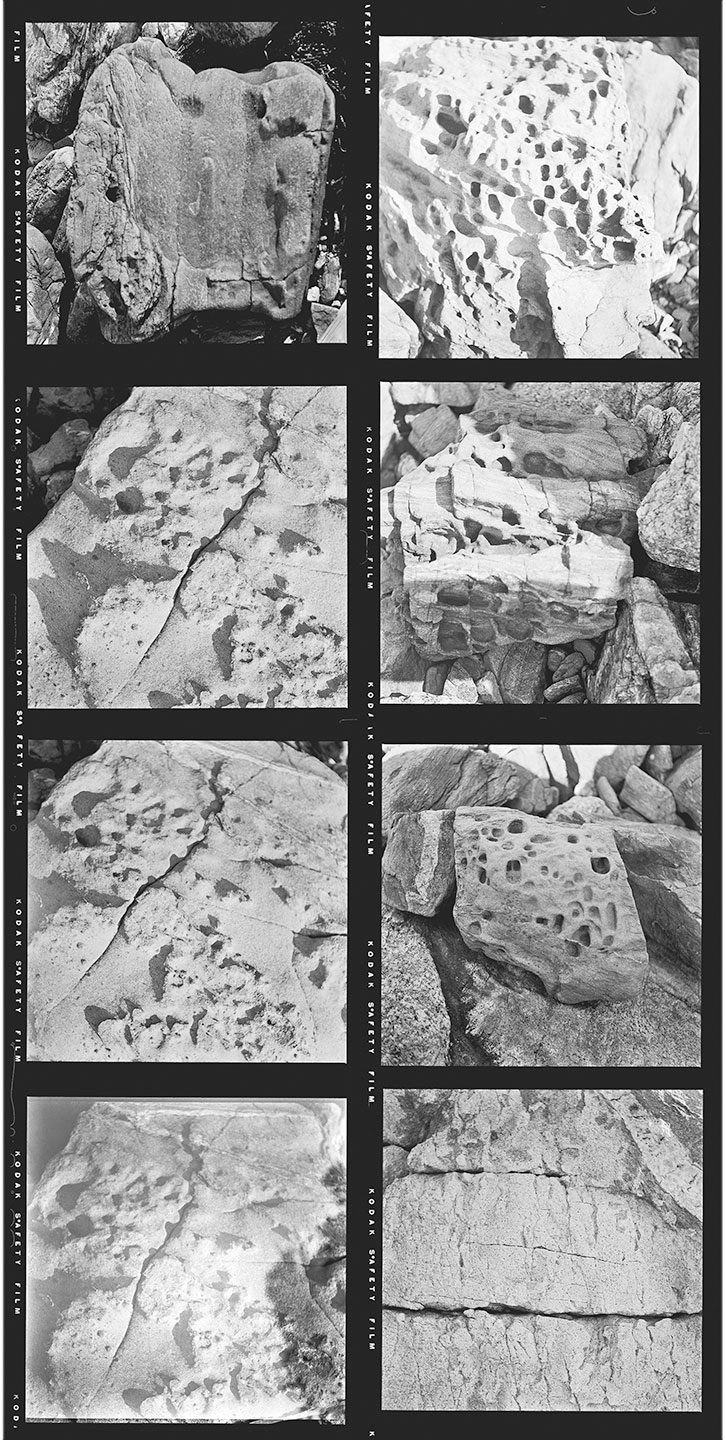

Untitled (Contact Sheet with Close-ups of Rocks), 1931

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 5 in. (25.4 x 12.7 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled, c. 1932–35

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

7 x 9 ½ in. (17.8 x 24.1 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Untitled (Waterlilies), c. 1932–35

Chromogenic black-and-white print of photocollage

9 ½ x 13 in. (24.1 x 33 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Circle and Box” with “Untitled 1963” (and Other Works in Background), Bolton Landing, 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

“Circle and Box” with “Untitled 1963”, Bolton Landing, 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

This image exemplifies Smith’s tendency to photograph his sculptures from a “worm’s-eye” view. In addition to suggesting monumentality, this technique of capturing a work from below accentuates the patterns and shapes of the shadows cast by the unique reliefs and planes of the sculptures’ forms. Likewise, photographing from this angle gave Smith the opportunity to align the base of the sculptures with the natural horizon line of the grassy field at Bolton Landing; the monochromatic white surface allows the sculptures to cast geometric shadows, recede into the clouds, and reappear against an open sky—demonstrating Smith’s interest in confusing two- and three-dimensionality. As with many of the photographs Smith took of his sculptures from the mid-1940s onward, this image gives the viewer a snapshot of how the artist understood his own works, untenable forms that change depending on the viewer’s position and the natural setting.

Molds for “Head as Still Life I”, 1942, and “Head as Still Life II” at Bolton Landing, 1942

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Sculpture Group: Freshly Painted Outside Workshop (Top) and in Workshop (Middle

and Bottom), 1961

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Group at Bolton Landing with “Primo Piano I”, c. 1963

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Dan Budnik

American, b. 1933

Bird’s-Eye View of the North Field, David Smith’s Home, and Portion of South Field at Bolton Landing, New York, c. 1962

Chromogenic black-and-white print, exhibition copy

11 x 9 in. (27.9 x 22.9 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

When this photograph was taken, the fields surrounding Smith’s home and studio in Bolton Landing were becoming increasingly populated with sculpture; by the time of his death, in 1965, the artist had placed eighty-nine sculptures outdoors. Photographer Dan Budnik went to Bolton Landing in December 1962, the first of many visits he would pay to Smith’s remote home. In this aerial view, Budnik demonstrates how Smith methodically installed works along a grid. He would later recall, “Images of David stick with me. . . . My contact sheets are alive with his thoughts; his work exudes life. He showed me his fields of sculpture and shared his vision too.” The photographs that followed Budnik’s visit to Bolton Landing have become some of the most iconic images of Smith in his studio.

Unknown photographer

Portrait of David Smith with “Primo Piano I”, 1962

Chromogenic color print, exhibition copy

8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

The Estate of David Smith, New York

Albany I, 1959

Painted steel

25 x 25 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (63.5 x 65.4 x 18.4 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Becca, 1964

Steel

78 x 47 1/2 x 23 1/2 in. (198.1 x 120.7 x 59.7 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

XI Books III Apples, 1959

Stainless Steel

94 x 35 x 16 1/4 in. (238.8 x 88.9 x 41.3 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Five Units Equal, 1956

Painted Steel

73 1/3 x 16 x 14 in. (186.3 x 40.6 x 35.6 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

The Iron Woman, 1954-58

Painted Steel

88 1/4 x 14 1/3 x 16 in. (224.2 x 36.4 x 40.6 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Personage of May, 1957

Bronze

71 5/8 x 31 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. (181.9 x 80 x 47 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Portrait of a Lady Painter, 1954/1956–57

Bronze

64 x 59 3/4 x 12 1/2 in. (162.6 x 151.8 x 31.8 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

Raven V, 1959

Steel and stainless steel

59 x 55 x 11 in. (149.9 x 139.7 x 28 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation

The Sitting Printer, 1954-55

Bronze

87 x 15 3/4 x 17 in. (221 x 40 x 43.2 cm)

Gift of the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation